Disk encryption is one of several physical security measures that could be used to protect data on your computer from unauthorized physical access. And it is best configured during installation, not after. But once configured, how effective is it?

First, let’s see how it is implemented in some popular Linux distributions.

In Fedora, for example, all you need to encrypt a whole disk, other than the boot partition, is enable the “Encrypt disk” option. In versions of Fedora before Fedora 16, the latest stable edition, that creates an encrypted LVM installation. LVM, the Linux Logical Volume Manager, is a flexible disk management system. However, in Fedora 16, enabling that option could also create an encrypted, non-LVM installation, if the “Use LVM” option is unchecked (disabled).

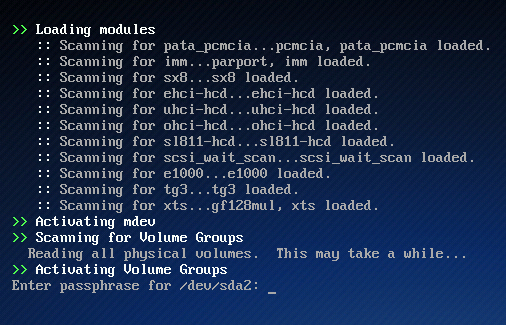

Whether using LVM or not, the effect, once the disk is encrypted, is the same. The system will not boot if the encryption passphrase is not entered correctly. The screen shot below shows the encryption passphrase prompt at boot time.

The same happens with an encrypted installation of Sabayon, a Gentoo-based Linux distribution that makes use of a modified version of Anaconda, the Fedora system installer. Its passphrase-prompt screen is just prettier.

But the effect, as stated earlier, is the same. The system will not boot if the correct passphrase is not entered. That Means if you forget your computer somewhere, or if it is stolen, you data is protected. You might never recover your computer, but you know at least that without access to the passphrase, your data will remain secure, save from viewing by unauthorized eyes. But what if an entity with more resources than a petty thief gets physical access to your computer. Can they bypass the physical barrier posed by the encryption scheme?

Writing for PhysOrg.com, Bob Yirka reports that:

A joint U.S./UK research team has found that common encryption techniques are so good that law enforcement, from local to highly resourceful federal agencies, are unable to get at data on a computer hard disk that could be used to prove the guilt of people using the computer to perpetuate crimes.

The study’s report is available as a paid download. However, the abstract is freely available. In part, it says that:

The increasing use of full disk encryption (FDE) can significantly hamper digital investigations, potentially preventing access to all digital evidence in a case. The practice of shutting down an evidential computer is not an acceptable technique when dealing with FDE or even volume encryption because it may result in all data on the device being rendered inaccessible for forensic examination. To address this challenge, there is a pressing need for more effective on-scene capabilities to detect and preserve encryption prior to pulling the plug.

So, we know that encryption a disk does protect your data from a petty thief to local and federal authorities. While the study’s focus was on criminals, we know from recent reports that the term “criminal” can be applied to anybody before it is even proven that they have committed a crime. Local and/or federal authorities could show up at your dorm room, house or work place and seize any computing device in sight, even when they do not have a valid legal reason or reasons to do so.

Back in early 2009, for example, a Boston College computer student had to ask a judge to “quash an invalid search warrant for his dorm room that resulted in campus police illegally seizing several computers, an iPod, a cell phone, and other technology.”

The case made its way up to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts where it was tossed out. The ruling was that the search warrant was obtained on fraudulent grounds. Some of the reasons (given for the search warrant) were:

… the student being seen with “unknown laptop computers,” which he “says” he was fixing for other students; the student uses multiple names to log on to his computer; and the student uses two different operating systems, including one that is not the “regular B.C. operating system” but instead has “a black screen with white font which he uses prompt commands on.”

Whether the reasons were justified or not is immaterial. The fact is without encryption, the authorities had easy access to all the data on the seized computing devices.

The point of this article is, you do not have to be a criminal before you need to take appropriate measures to safeguard your private information from unauthorized access. You do not have to have something to hide either. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has published a Know Your Rights and Surveillance Self-Defense guides. They are a good read.

Plausible deniability is the required addition if you expect dealing with someone more powerful than a thief.

There is actually password saved, in your head, and people who needs it are good at retrieving it from there.

Depending on country they may either stick needles under your nails or force you legally to reveal the pass.

So, it’s actually vulnerable to non-technical attacks like such.

Another option is a mechanism to wipe all data somehow quickly.

Another drawback of whole-volume encryption is its all-or-nothing approach. One key grants access to many files. MAC/RBAC can mitigate this, but file-level encryption with discrete keys can take information security to a whole new level.

The idea is if an unauthorized person cannot read the drive, job is done. However, there is nothing wrong in having more than one level of encryption.

Encrypt the disk, and encrypt files and folders that you really, really want to keep private.

Multiple encryption is not a good idea. Two ciphers together can be weaker than either cipher alone.

Not if one has nothing to do with the other.

Any encode/encryption method only requires something.

That something is the key to decode, simple. 99.9% of geeks

will start with that fact. Guess who reads fastest, citizen

or super Ucpu. Automated attacks answer is done for that reason.

If U need is worth it, bribe local geek.

It is good to know that disk encryption does not protect against “evil maid”. If you leave your computer in hotel and there is an evil maid (read: some geek) that replaces boot partition program with some evil keylogger and then you come back to hotel, type in the password that key-logger stores on boot partition and you just start working as normal, leave hotel with your computer in the hotel and evil maid has got your password and can log-in into encrypted disk.

Similar by less technical maid could do with secret cam that is filming your fingers while you are typing a password.

So there is no 100% security.

I have seen a company that had a policy that you had to remove the hard disk from your computer and leave only bare bone laptop in hotel.

In this case still possible (but harder) to replace BIOS program with some key-logger etc. There is just never 100% of security if you like it or no.

But bare in mind, more measures you take less likely the person with knowledge and the will will brake your system.

Physical security goes beyond more than just hard disk encryption. You might want to read this.

Good to know.